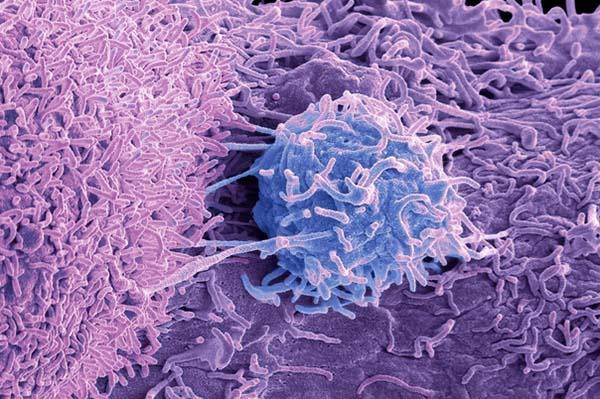

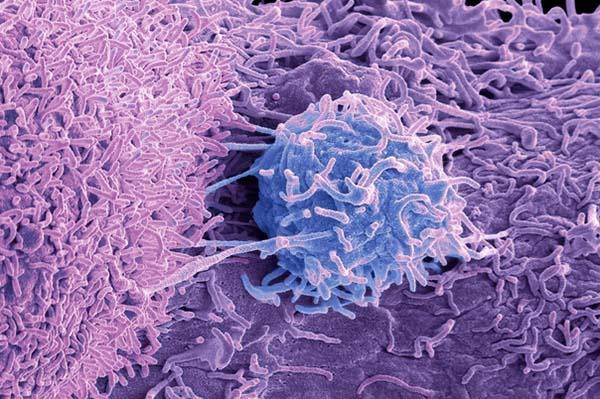

Metastatic prostate cancer can progress in different ways. In some men the disease advances rapidly, while other men have slower-growing cancer and a better prognosis. Researchers are developing various tools for predicting how fast prostate cancer might progress. Among the most promising are assays that count circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood samples.

Prostate cancer spreads by shedding CTCs into the bloodstream, so higher counts in blood generally reflect worse disease. Sometimes referred to as a liquid biopsy, the CTC assay can help doctors decide if patients should get standard or more aggressive treatment. Just one CTC assay is currently on the market for prostate cancer. Called CellSearch, its use is so far limited to men with late-stage metastatic cancer for whom hormonal therapies are no longer effective.

Using CTC data

Hormonal therapies block testosterone, a hormone that drives prostate tumors to grow. Research shows that high CTC counts predict poorer survival and faster disease progression among patients with metastatic prostate cancer who become resistant to this form of treatment. But new research shows CTC counts are also predictive for early-stage metastatic prostate cancer that still responds to hormonal therapy.

Why is that important? Because the earlier doctors can predict a cancer’s trajectory, the better their ability to select patients who could benefit from more powerful (and potentially more aggressive) drug combinations or a clinical trial. Conversely, men who are older or frail might be treated less aggressively if doctors had better insights into their prognosis.

How the study was done

The investigators collected blood samples from 503 newly-diagnosed patients with hormonally-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer who had enrolled in a clinical trial with experimental hormonal therapies. The team collected baseline samples at trial registration, and then another set of samples after the treatments were no longer working. CTC counts were divided in three categories:

- more than 5 CTCs per 7.5 milliliters (mLs) of blood

- between 1 and 4 CTCs per 7.5 mLs of blood

- zero CTCs per 7.5 mLs of blood.

What the research showed

Results showed that men with higher baseline CTC counts fared worse regardless of which cancer drugs they were taking. Median survival for men with 5 or more CTCs per sample was 27.9 months compared to 56.2 months in men with 1 to 4 CTCs. There weren’t enough patient deaths among those with 0 CTCs to calculate a survival rate.

Similarly, higher CTC counts predicted faster onset of resistance to hormonal therapy: 11.3 months for men in the highest CTC category, compared to 20.7 months and 59 months for men with 1 to 4 and zero CTCs respectively. Importantly, higher CTC counts correlated with measures of prostate cancer severity, including PSA levels, numbers of metastases in bone, and other indicators.

Observations and comments

“This research emphasizes the continued emergence of CTCs in helping to determine outcomes and potentially treatment options for men with metastatic prostate cancer,” said Dr. Marc Garnick, the Gorman Brothers Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and editor in chief of the Harvard Medical School Guide to Prostate Diseases.

“Still to be determined is how this type of testing compares with more traditional evaluations of disease advancement, such as x-rays, bone scans, and other types of imaging. Ready access to cancer cells in blood that, in turn, eliminate the need for more invasive biopsy procedures of metastatic deposits will be a welcome addition — especially if future studies show that CTCs inform more precise treatment choices.”

Dr. David Einstein, a medical oncologist specializing in genitourinary cancers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, agreed with that assessment. “But the Holy Grail is finding predictive biomarkers [like CTCs] that tell you if patients will or will not benefit from particular treatments,” he added. “Answering these types of questions requires randomized clinical trials.”

About the Author

Charlie Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

Charlie Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, Charlie has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by Charlie Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD